Visualizations

The initial report from the project can be found here. The network approach allows us to focus our attention primarily on the interactions within any given system, whether that be a world of letters, journeys etc. The bigger the data however, the harder it is to deal with. This database is currently one corpus of letters–-there are 600 letters-–centered around one particularly important figure at the time, George Melville, Lord Melville, the Secretary of State for Scotland. The letters exchanged in this period are more than just networks of correspondence; people were bound together through community, print, and dialogue. Exchanging letters in a period of chaotic and often violent warfare was even more complex. Context is everything in understanding people, groups, identity, and behavior in the early modern world. Given this, understanding the relationships is paramount to visualizing the data. Behavior, relationships, and identity changed over the course of the Revolution and Networking Letters of the Revolution sought to trace those changes and connect historical networks with visual interpretation by building a new database and visual representation of the interconnected nature of communication. In the last 25 years, there has been a noticeable shift from historical records remaining piecemeal or fragmented in boxes in archives to a sea of digitized images and texts in the form of PDFs or PNGs. A number of manuscripts are now available online, including the Leven and Melville Papers. Our goals in this project were to:

- Visualize the world of communication from a corpora of letters.

- Understand communication patterns during conflict and a regime change.

- Parse group dynamics and information distribution from a chaotic period of transition.

- Democratize the pursuit of knowledge and expand the potential for research in this area of research.

This project is a marriage of early modern Scottish history and computational data science. It brings together methods of network science, prosopography, and traditional early modern political history surrounding communication. The visualizations show a story of connectivity over time. We chose this particular corpus of letters because Leven and Melville Papers do a very good job at capturing the difficulties in the reconstruction and administration of Scottish governance during such a chaotic period.

Methodology

Phase one required turning qualitative data into quantitative data. We started by recording all of the pertinent data from the PDF version of the Leven and Melville Papers. We then turned this data into spreadsheet data, here we used categories: Id, Sender, Receiver, Location from, Location to, Latitude and Longitude, Type and Date. This allowed us to parse the networking data in the form of nodes and edges. The data was then cleaned using OpenRefine to split up latitude and longitude and keywords into different columns; we also made sure there were no blank tiles and duplicates. After creating a master spreadsheet information file, we then set about creating different sheets for different visualizations including people, places, keywords, nodes, and then edges (relationships). We were able to get all the data from the 599 letters contained in the digitized copy of the Leven and Melville papers into a csv file. Given the large dataset of Network Letters, it allowed for exploratory data analysis and investigation on different digital tools to identify the best representation of the relationships presented in the papers. One of the main tools we ended up using was the programming language Python; which contains a large number of libraries that extend the capabilities of the language, allowing for complex visualizations of the Network Data. One of the most prominent libraries used was networkx, which allowed the creation of network graphs along with the application of the Girvan-Newman algorithm to detect communities within the network. This algorithm works by repeatedly removing edges on the shortest path within the network. Additionally, the nodes are given corresponding colors to highlight their community, enabling an easier identification of groups in the network. The algorithm is important for understanding the network graph because a node with higher betweenness centrality would have more control over the network, due to the fact that more information will pass through that node. The implementation of these libraries and creation of visuals were carried out on Jupyter notebook, which is an open-source software for interactive computing. In addition, we experimented with tools such as Leaflet, Flourish, and Gephi for further analysis of the letters.

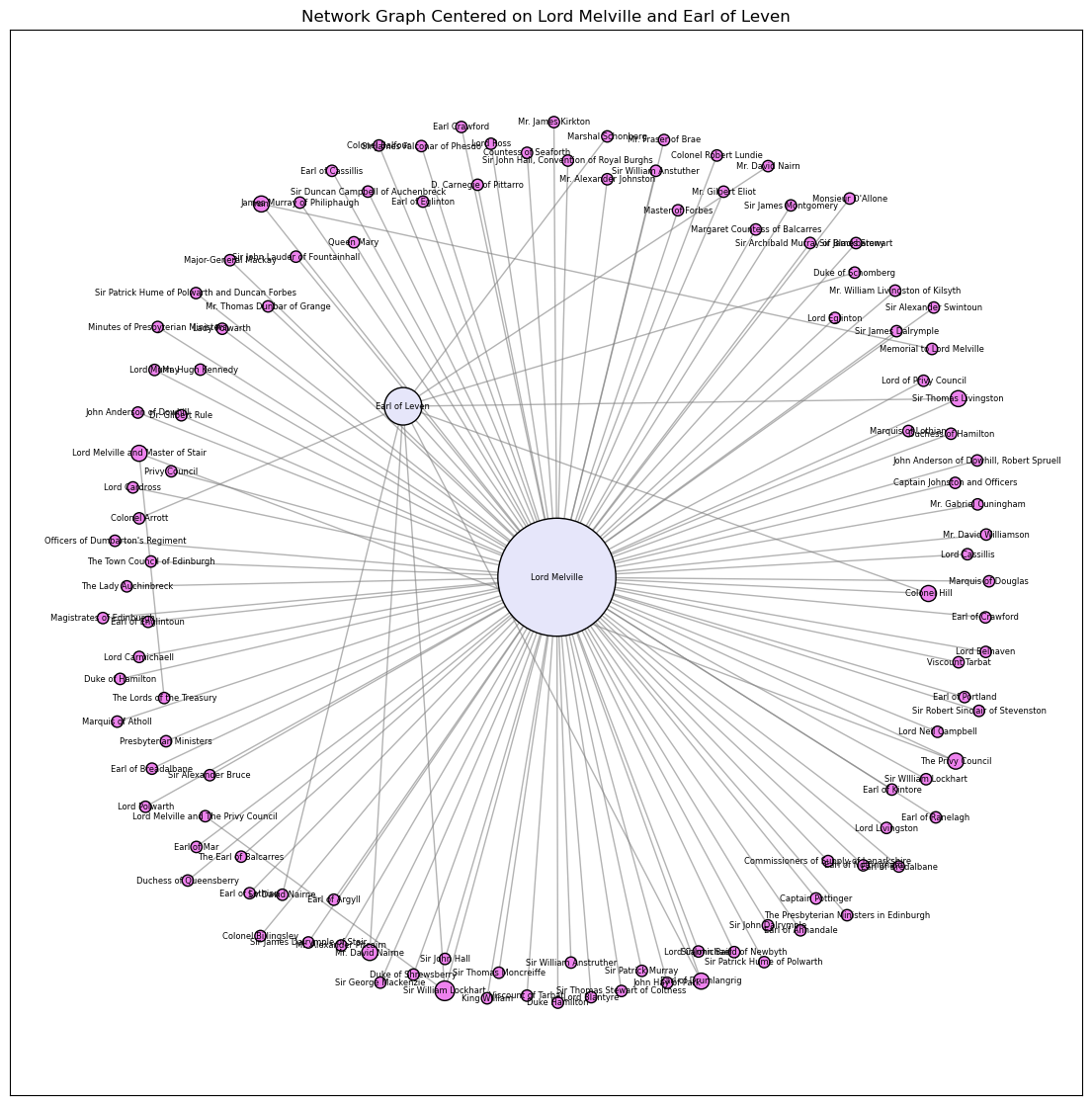

Degree Centrality

Our exploration began with a degree centrality analysis of the letter corpus. This is a calculation of the number of edges or connections of a singular node. Degree centrality is the easiest calculation of the significance of the node on the network i.e. where it is structurally important and often reveals clusters that dominate the network. Unsurprisingly, Melville has the largest centrality count of 499, he is followed by Crawford with a score of 87, Hamilton with a score of 56, and John Dalrymple of Stair with 46. This measure is useful for thinking about hierarchy and power dyanmics within the new regime. Many people wrote to the Secretary of State for many different reasons, most commonly individuals wrote asking for favor or giving updates or opinions on the ongoing situation in Scotland-whether that was the Highland War, the siege in Londonderry, or difficulties in parliament or settling the religion. For example, Sir Thomas Livingston wrote to Melville in 1691 saying "Since my last [letter], there is nothing occured of moment here... We have the news here that four French men of war are come to the Isle of Skye, and brought ammunition, arms, provisions, and officers."1 This overview is important since Melville was directly connected to the King and his primary source of information about Scotland's affairs, even into 1691 when things were supposedly cooling down. It is important to note, that this corpus is highly skewed toward Melville and Leven since it is a printed collection of their surviving correspondence.

Most Connected Nodes

What we have found within this corpus is 123 unique senders and receivers; each was assigned metadata in the form of their allegiance, cabinet position, and weight. We found 554 individual letters, packets, orders, sets of instructions, declarations, commissions, attestations, memorials, intercepted letters, and more. The corpus also contained 72 places of origin and target which were then geocoded. We aregues similarly to Ruth and Sebastian Ahnert's suggestions that network hubs correspond broadly with the centers of government.2 This also includes somewhat symbolic hubs of the monarch and the principal secretaries. There are imbalances present throughout the corpus especially since more letters received survive than letters sent. If there was a complete record of the correspondence there would be less imbalance. There are also intercepted letters present in the collection which might account for some of the anomalies in the network.

After some initial calculations and experimentations, we argue that based on the letters contained in the corpus the most connected nodes are Melville, King William, Queen Mary, William Lockhart, the Earl of Crawford, the Earl of Leven, Colonel Hill, and the Privy Council. This is unsurprising since the monarch and their principal secretaries tend to be the same epistolary hub. The Earl of Crawford and the Privy Council served as the primary contacts for the Scottish administration for much of the time period. William Lockhart served as Solicitor General for Scotland from 1689 to 1693 and was the King's principal legal advisor for Scottish affairs. Leven and Hill served as the governors of Edinburgh Castle and Fort William (Inverlochy) and had many military connections and networks. That these are the most connected nodes speaks to the amount of letters that were exchanged about the evolving situation in Scotland. Despite instructions contained within many of the letters, which told the receiver to burn the letter received, correspondence from the period has survived. In aggregate it shows that despite previous assertions that William was not interested what was going on in his northern kingdom we can argue that this seems not to be the case.

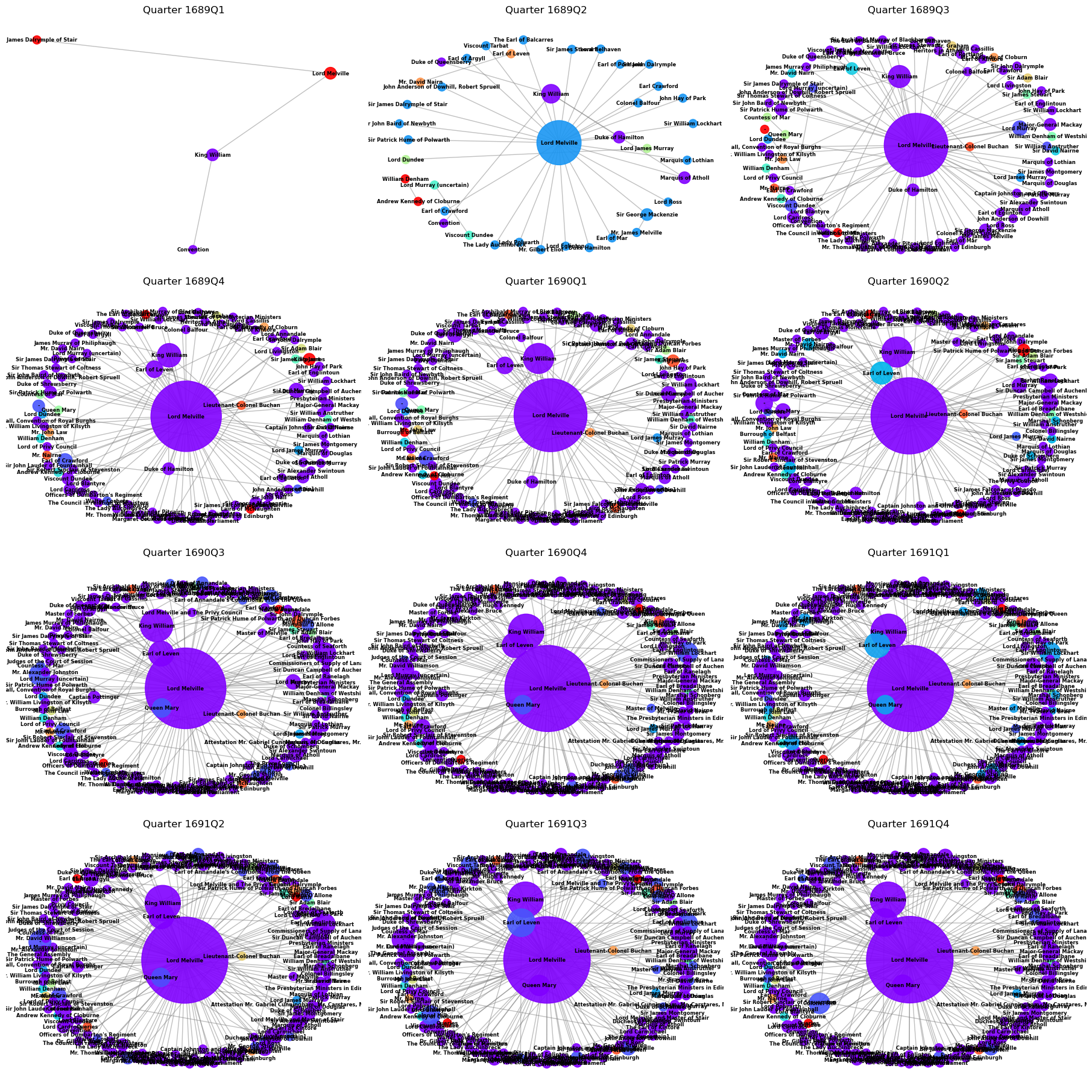

The quarterly visualization shows just how connected the people in this corpus of letters were over the course of three years. Lord Melville is depicted by the large purple node present in each diagram as both a sender and a receiver of letters – since he is either the letter writer or letter receiver in 510 of the 599 documents within the corpus. As a node, Melville has the highest infrastructural role in the network, followed by the Duke of Hamilton (High Commissioner to the Scottish Parliament), his successor the Earl of Crawford, and then the monarch himself. The diagrams also indicate an increased density of networks over time. It also shows the density of specifically the Williamite network since the early part of 1689 contained many Jacobite sympathizers (which is why we see the Viscount of Dundee, James's military general and Lord Murray), and their names seem to disappear over time while Melville's centrality to the network grows as we see his purple node growing larger from 1689 through 1691. It also becomes clear that Melville is an imortant bridge from one network to another, as the Secretary of State for Scotland this is somewhat unsurprising.

The subplots here show quarterly accounts of the communications in the Leven and Melville Papers over the course of the revolutionary period. The plots which match Melville - in purple or violet - are all directly connected to Melville and either sent or received a letter from him. Those nodes in other colors are the outliers that either corresponded only with another node in the collection or are letters that were intercepted by the Secrtary of State's employees. As Melville's network becomes denser, his receiving node grows in size, indicating that he received more letters over time. This correspondense activity reached its peak density in the fourth quarter of 1690 and maintained that denstiy throughout 1691. The Earl of Leven on the graph is also connected to Melville since they are related and exchanged letters. They are also indirectly connected by multiple bridges and social spheres different social spheres. For example, the Duke of Hamilton as High Commissioner to the Scottish Parliament in 1689, acts as a bridge between them. The plots are also directional and show the direction of communications as Melville appears as both a node for sending and receiving letters. Melville received 447 letters over the course of the corpus but only sent 31 whereas the Earl of Crawford sent 81 letters and received 6 (but this might speak more to the practices of privacy between elite correspondence in the 17th century).

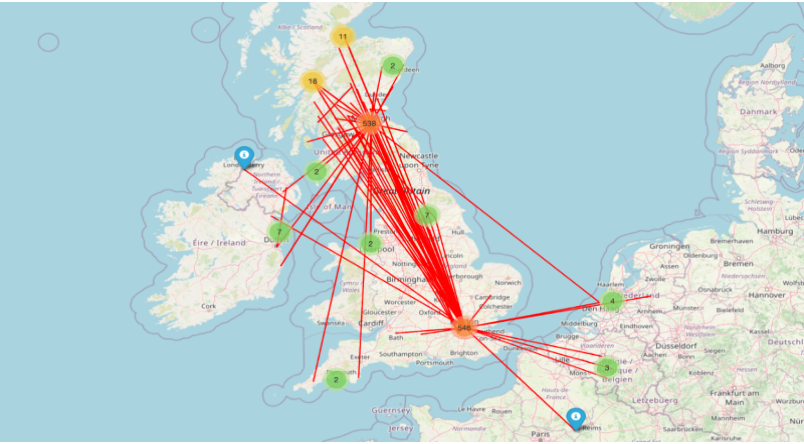

Geography and Place

Despite the fact that William never set foot in Scotland, the considerable two-way flow of correspondence between Edinburgh and London, combined with the numerous journeys made by officers of state, meant that he had a great deal of information about the situation in Scotland and was able to relay instructions to his Scottish counterparts. The high traffic of post and letters referring to the situation in Scotland suggests that the secretaries stayed in frequent contact with their counterparts in Edinburgh. One of the things that is evident from the graph produced by the Leaflet libraries is that the network expanded more than just Scotland and England, letters in Melville's corpus ranged from Dublin and Ballyhara in Ireland to Brussells and Gerpines on the continent. The largest clusters were in Edinburgh and London which is unsurprising since William's most important ministers resided in the respective captials and centers of governance.

Smaller clusters existed at Tarbat and Inverlochy/Fort William which became a very important node of the military campaign from 1690 to 1691. A flurry of letters and a memorial to Melville from the Viscount of Tarbat between June and July in 1689 accounts for another smaller cluster. Tarbat had been part of James' cabinet and was exonerated by William, therefore wrote to Melville often offering advice and opinions on the church and governance. Clusters in London tended to center on Hampton Court and Kensington where the King tended to be. The cluster in Ireland can be accounted for both by the intercepted letters from James and William's travels before and after the Battle of the Boyne.